If the other parent takes your child from their home in Australia to another country without your permission, this is known as international child abduction. You should obtain prompt legal advice if this happens to you about your rights and options to facilitate the swift return of your child to Australia. The first question your lawyer will ask you is, whether the country that your child has been removed to is a Hague Convention country or a Non-Hague Convention country. In other words, whether the country that the child has been taken to is a signatory to the Hague Convention.

If your child is abducted from Australia, then the difficulty associated with having your child returned to Australia will depend on whether the country that the child has been taken to is a signatory to the Hague Convention.

What is a Hague Convention Country vs a non-Hague Convention Country?

The Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction is an international agreement between various countries about the process when a child is abducted and wrongfully removed from or retained in Australia.

The primary object of the Hague Convention (and the Regulations) is to secure the prompt return of a child who has been wrongly removed from one convention country to another, or has been wrongfully retained in a convention country.

The purpose of the The Hague Convention Regulations is to give legal affect to the Hague Convention on Child Abduction, in Australia: s111B of the Family Law Act.

But what if your child has been removed to a country that is not a signatory to the Hague Convention, such as Bali, Russia, India or Iraq?

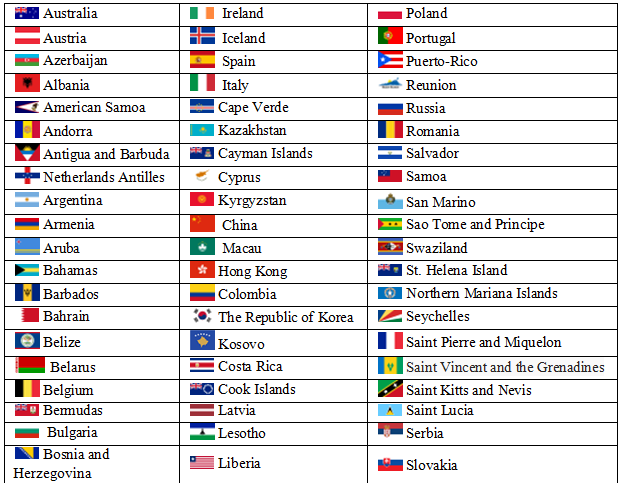

The list of countries that are a signatory to the Hague Convention is accessible here and also set out in the image below:

If your child is in a country which has not signed and ratified the Hague Convention such that they agree to become a party to it, you cannot seek your child’s return to Australia under the Hague Convention, and it will be more difficult to recover your child and have them returned to Australia.

My child might be taken from Australia to a Non-Hague Convention Country without my consent

You should seek urgent legal advice about your rights and options, in the individual circumstances of your case.

Prevention is always better than cure.

If your child is still in Australia and you are worried that the child will be taken by the other parent overseas without your consent, to a Hague / non-Hague Convention country, there are various options available to you.

Firstly, you should retain the child’s passport. Also check out our article on Airport Watchlist orders, which describes preventative measures you can take in order to stop your child from being removed from Australia in the first place.

My child has been taken from Australia to a Hague Convention Country

You should seek urgent legal advice from a family lawyer about your rights and options.

In applications under the Hague Convention, the Court is not subject to the principle that the best interests of the child is the paramount consideration, albeit the child’s best interests is likely to be a significant and weighty matter.

For more information on making an application for return of your child that has been taken to a Hague Convention country, check out our page on International Child Abduction.

My child has been taken from Australia to a Non-Hague Convention Country

If your child has been unilaterally removed from Australia to a Non-Hague Convention Country, the preliminary steps that we recommend you take, are as follows:

- you should seek legal advice from a family lawyer immediately. Delay can negatively impact the prospects of having your child returned to Australia.

- Maintain respectful communication with the other parent. Abusing or threatening the other parent will not assist you in your goal of having the child returned to Australia.

- Maintain frequent communication with your child. Don’t involve them in the adult issues as this will worry and upset the child. Tell them that you love them and that you will see then as soon as possible.

- Find out the location of your child. Do some research. Family and friends may be able to reveal their location. Alternatively bank statements or social media may provide a clue as to where your child is. If the child is older, they may be able to tell you where they are.

- Attempt to negotiate the return of the child with the other parent, either directly or through your lawyer. Your Family Lawyer may be able to convince the other parent to return without the necessity of legal action.

- Compile your evidence of communication with the other parent at all relevant times, including prior to and after the removal of your child from Australia. Records of your communication with the other parent confirming you did not agree to the child being removed from Australia will be vitally important.

- Consult a family lawyer in the non-Hague Convention Country to ascertain your rights, the process and your prospects of success if you were to commence proceedings in that country for the urgent return of your child.

- If the other parent refuses to return, discuss with your lawyer filing an application in the Family Court of Australia seeking return of your child.

What is the process if applying for return of my child in a Non-Hague Convention Country?

It is more difficult, but not impossible to have your child returned to Australia if your child has been removed to a Non-Hague Convention Country.

If you have Australian parenting orders which provide that you have parental responsibility for your child and rights to spend time with your child, this will assist in having your child returned to Australia and you may be able to seek enforcement of those orders under the laws of the Non-Hague Convention Country. Even if the Australian parenting order is not enforceable in the foreign country, it may be relevant in determining the parenting dispute under the laws of that country.

But is it possible to apply to the family law courts in Australia to seek the return of your child if they are in a Non-Hague Convention Country? The simple answer is yes, it is possible, but it depends on the circumstances of your case.

The first question that needs to be answered in determining whether you can apply to the Australian family law courts to have your child returned from a Non-Hague Convention country is – whether the Australian Court or authorities have the jurisdiction to determine the issue of return of your child to Australia.

The relevant legislation that determines whether Australia has jurisdiction to hear an application for the return of a child to Australia from a Non-Hague Convention country is s69E and s111C and s111D of the Family Law Act:

s69E Family Law Act

Section 69E(1) states that proceedings may be instituted in Australia under the Family Law Act regarding a child if:

- child is present in Australia on relevant day; or

- child is Australia citizen/ordinarily resident in Australia on the relevant day; or

- a parent of the child is an Australia citizen/ordinarily resident in Australia/present in Australia on the relevant day; or

- a party to the proceedings is an Australia citizen, ordinarily resident/present in Australia on the relevant day; or

- it would be in accordance with a treaty or arrangement in force between Australia and an overseas jurisdiction, or the common law rules of private international law, for the court to exercise jurisdiction in the proceedings.

For the purpose of the section, the ‘relevant day’ is the day the application is filed: s69E(2).

In summary, the child or the parent must, at the least, be present in Australia on the date the application for parenting orders is filed.

Under s4 of the Family Law Act, ‘ordinary resident’ means habitually resident.

s111CD Family Law Act

Section 111CD, under the heading ‘JURISDICTION RELATING TO THE PERSON OF A CHILD’ states:

(1) A court may exercise jurisdiction for a Cth personal protection measure only re:

- a child who is present and habitually resident in Australia; or

- a child who is present in a non-Convention country, if:

- the child is habitually resident in Australia; and

- any of paragraphs 69E(1)(b) to (e) applies to the child.

A ‘Commonwealth personal protection measure’ is defined in section 111CA as:

‘ .. .a measure (within the meaning of the Child Protection Convention) under this Act that is directed to the protection of the person of the child.’

Case Example: Chandra & Chandra

In Chandra & Chandra [2017] FCCA 451 the court was required to determine whether it had jurisdiction to hear an application by the mother for parenting orders where the subject child was born in Australia, the child was an Australian citizen but the child was living in India.

The Court held that it would only have jurisdiction to make a parenting order if under s111CD the subject child was habitually resident in Australia on the day of filing the application and any of the subsections under section 69E1(b) – applied such that the subject child or parent was present in Australia on the day the application filed.

In this case, the Court determined that habitual residence of the child was in India and therefore the Court did not have jurisdiction to hear the matter.

Case Example: Mendelson & Kerner

In Mendelson & Kerner [2018] FCCA 3344, the Court held that it had jurisdiction under s69E to make parenting orders despite the child being present in a Non-Hague Convention country as the 15 month old child was still ‘habitually resident’ (albeit not present) in Australia at the time of the father’s application to the court.

The Facts

The child was unilaterally taken by the mother to a Non-Hague Convention country.

The parents were in Australia on student visas when the child was born in Australia. The child lived in Australia for eight months but was unilaterally taken by the mother to stay with the child’s maternal grandmother in a Non-Hague Convention country overseas, three weeks prior to the father bringing his application for parenting orders.

To have jurisdiction under s69E to hear the Father’s application, the Court had to determine whether either the child or the parent was present in Australia on the day the application is filed.

The Decision

After noting that s69E(1) of the Act was not satisfied as the child was not present in Australia on the day of the application being filed, but the section was satisfied by virtue of the fact that the Father, being a party to the proceedings, was ordinarily resident in Australia on that day, the court cited the notation in s 69E(2) which reads “Division 4 of Part XIIIAA (International protection of children) has effect despite this section”. This section deals with jurisdiction for the person of a child.

The Judge surmised that s69E must be read subject to s111CC and s111CD of the Family Law Act which provides a series of qualifying connections that must apply before the Court can exercise jurisdiction.

s111CC was irrelevant in this case.

The Court reviewed s111CD (set out above) and when read in conjunction with s69E(1), noted that the Court has jurisdiction to make a parenting order in this case in relation to the child, who is prevent in a Non-Hague Convention country, only if the child was habitually resident in Australia on the day the Father filed his Application.

Neither the term ‘habitual residence’ nor ‘habitually resident’ is defined either in the Child Protection Convention or the Family Law Act so the Court had to form its own view about the meaning of ‘habitual residence’.

The Court noted the following when determining the child’s habitual residence on the date the father’s application was filed:

- On the date that the father applied to the Court, the child had been living in Australia for ten months, and then in the Non-Hague Convention Country for a little over three weeks.

- It is difficult to see how the child could have relinquished his ‘habitual residence’, which until 2018 had undoubtedly been in Australia, in the three weeks since the child had been taken from Australia;

- The child had at that stage spent his whole life in Australia, was taken to the Non-Hague Convention country without his father’s knowledge or consent on in 2018. His mother left him there with her mother and returned to Australia, she says, until at least 2021. She was in the Non-Hague Convention Country for less than two weeks … In those circumstances, there might be some force in an argument that she was habitually resident in Australia on the date the Father’s application was filed.

- It was only after the father had filed his application that he discovered that the child was not in Australia. As far as he knew, the child was in Australia on the day he filed that application.

In these circumstances, the Court made the following findings, that on the date of the father’s application:

- The child had been living in Australia for 10 months and in non-hague country for 3 weeks;

- As there is equivocal evidence as to whether the mother intended him to remain indefinitely in the Non-Hague Convention country at the time she took him or at time she left him there to return to Australia;

- As the father never consented to the child being taken to the Non-Hague Convention country –

- The child was not ‘habitually resident’ in the Non-Hague Convention country (as applicable to the child protection convention)

- The child was habitually resident in Australia despite not being present in Australia on the day the application was filed.

Therefore, the Court held that it had jurisdiction under s69E of the Family Law Act, to make parenting orders in relation to the child.

Are you concerned your child may be / has been abducted to a Hague / Non-Hague Convention Country?

We highly recommend you contact one of our experienced family lawyers to obtain prompt legal advice about your rights and the process to ensure the prompt return of your child to Australia.

Contact us to book a reduced rate initial consultation to have a confidential discussion about your individual circumstances.